by Bernarda Carranza, Martin Johaim, Jelena Malkowski

Demonstrators pushed against plastic shields of police, who used pepper spray to disperse people in the crowd near the government headquarters in Quito, Ecuador. Several demonstration signs read “Motherhood by choice and not by rape”. The country’s position on the abortion situation comes in waves and in late 2019, a flood of anger and frustration filled the streets again. Despite developments that introduced the issue to a broader political discourse, the government representatives yet successfully fought off an important step of legalizing abortion.

Elsewhere, similar protests and political debates regarding the legal situation of abortion led to a different outcome: Germany just reformed its abortion law at the beginning of 2019. German physician Alicia Baier still thinks the steps taken were not enough: “Despite legal changes, the number of lawsuits against doctors who perform abortions and neutrally state on their website what abortion methods they offer has increased.” For that reason, later in 2019 she co-founded “Doctors for Choice”, an organisation that fights for better assistance and access for women when it comes to abortion.

Two countries that could not be more different yet share one very similar narrative: The problematic situation of abortion in both societies became more of a public political debate again, despite policies successfully brushing the issue under the carpet in the past.

Despite legal inaction, Ecuadorian women fight relentlessly

When feminists in Latin America refer to la marea verde or the “green wave” they are talking about a movement that fights to change restrictive laws around abortions in many countries in the region. When feminists in Latin America talk about la marea verde, other than sport a very noticeable green bandana around their necks or clenched at their fists, they mention the 2018 movement in Argentina that started it all with the hopes for decriminalizing abortion in the country. They were not successful, as parliament did not pass the law but nonetheless, they were able to start a massive movement in the Latin American region, where now a staple in women’s marches is to chant: “¡Será ley!” (It will be the law!).

In Ecuador, where unsafe abortions are one of the leading causes of maternal deaths, this chant resonates stronger than ever within feminist collectives. And it especially did so on September 17, 2019 when the National Assembly – that had been debating for months prior on a new bill that would legalize abortions in cases of rape – announced their vote: 65 in favour, 59 against, and 6 abstentions, it meant the law with the intent to decriminalize abortions in cases of rape (known in social media as #AbortoPorViolación) did not reach the 75 votes needed to pass.

The Legal Situation in Ecuador

The ban on abortion has been in place since the country’s first penal code in 1837. Back then, there was a total ban, and it was reformed in 1938 to include the two exceptions mentioned before. However, since then, it has remained pretty much the same (with minor vocabulary changes in 2014, where “mental disability” was implemented instead of the words “idiot” and “insane” and minimizing the prison sentence from one to five years, to six months to two years).

Ecuador’s Penal Code in article 149 and 150 states that abortion is only permitted in two cases: when a woman with a mental disability is raped or when a pregnant woman’s life is in imminent danger and all other options have been exhausted. Otherwise, women who get an abortion can face a prison sentence of six months to two years.

The night the National Assembly vote was announced, women – activists and women collectives – protested outside. “You chose the wrong path, you are condemning women and girls. It’s embarrassing that #AbortoPorViolación was not approved, we don’t expect anything from you and you still manage to disappoint us” reads a tweet by the feminist organization in Ecuador, Surkuna.

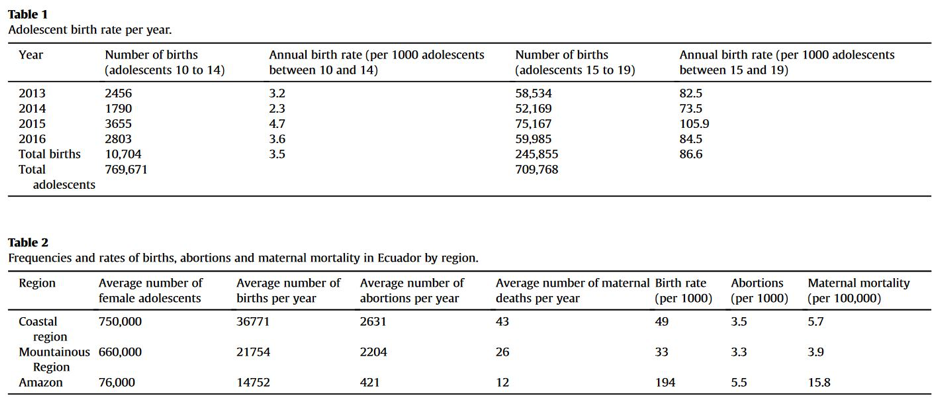

The lack of access to safe abortions, however, has not stopped women from seeking them. From 2004 to 2014, national statistics recorded 431,614 abortions. This number reflects abortions that were either medically justified, or cases in which women died after a clandestine abortion and when they were brought to the hospital, medical staff registered it as a maternal death due to abortion. The number can be even higher but due to the restrictive law, women who get clandestine or self-induce abortions are afraid to report them.

Organizations such as Surkuna, that specialize in advocating for women’s rights and providing legal assistance to women, have been fighting inside courtrooms and outside to change the country’s current law on abortion. “We provide legal counsel and defense, so we advise women on what they have to do within the judicial system and we also company them in these procedures,” says Ana Cristina Vera, lawyer and director of Surkuna.

Surkuna takes cases of gender violence and of women who have been criminalized for getting abortions. In the latter case, Vera adds that: “the women who come to Surkuna are mostly impoverished women, and women who are reported by health services or 911.”

According to Vera, most of the cases of women prosecuted because they had abortions taken by Surkuna have managed to stay within the first steps of the procedure, meaning that they did not go to trial and therefore the women were not sentenced. Nonetheless, from 2013 to 2017 a study found that 243 women were prosecuted in Ecuador for getting an abortion.

According to Vera, most of the cases of women prosecuted because they had abortions taken by Surkuna have managed to stay within the first steps of the procedure, meaning that they did not go to trial and therefore the women were not sentenced. Nonetheless, from 2013 to 2017 a study found that 243 women were prosecuted in Ecuador for getting an abortion.

What many activists have been protesting against is not only that women are criminalized or that they are dying as a result of lack of access to safe abortions but that in the context of Ecuador: girls and teenagers are forced to give birth. Ecuador holds the highest rate of teenage pregnancy in Latin America – 111 for every 1,000 pregnancies- and national statistics on births show that in 2018, 2,058 girls from the ages of 10 to 14 gave birth (the legal consent age in the country is 14, meaning that 100 percent of those girls were impregnated as a result of rape).

But in a country that is still very much Catholic and conservative, abortion continues to be taboo topic. “My vote will not go to allow abortion (…) I defend life, I defend life at conception because I don’t believe that the answer to our society’s serious problems is solved with violence,” claimed legistalor Esteban Torres during the National Assembly debates around the possible law reform. He is one of the biggest voices against abortion in the country.

Meanwhile, the reality for Ecuadorian women does not seem to improve. The most recent 2019 study conducted by the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Ecuador (INEC) showed that 65 percent of Ecuadorian women had suffered some type of violence or assault throughout their lives (either psychological, sexual, physical or patrimonial). This is a five percent increase since the last study on the subject in 2011. Most women reported having been victims of some type of violence either at the hands of their partner, someone in their social sphere or in their family. And in the last three years, according to figures from different organizations specialized in reproductive rights, 14.000 rapes had been reported in the country.

Despite the negative result of the National Assembly on the abortion bill, Vera believes that Ecuador’s mentality on the subject is slowly changing. “We have seen that [the mentality] has changed and there has been a different discourse on abortion at least since 2008 when I started working on the issue. (…) When I was an activist before 2008, a big part of the political action was also not to talk about the issue of abortion, it was like an agreement within the women’s movement. But now, abortion in cases of rape is becoming more accepted but the total decriminalization of abortion is more accepted also,” she claims.

The “green wave” that hit Ecuador continues to push back against legislators and their chant continues to resonate: “¡Será ley!”.

Germany: Aggravating circumstances for abortion are recurring

When Ulrike Müller* had her pregnancy terminated in 1983, there were still less exceptions from punishment for abortion in the Western German penal code: „I don’t remember what the exact legal situation was back then, but for me it was definitely not a problem to get an abortion,” Müller recounts today. Since she was still a student when she got pregnant at the age of 24, Müller was able to get an abortion on the base of social reasons and the ongoing women’s movement from the 70s was a support for her: “Back then there was a strong women’s movement against paragraph 218, women’s consultation centres and women protested for ‘my belly belongs to me’. The consultation centres were very supportive, and I was lucky to have a great, liberal and open gynaecologist.” That way, her abortion underwent quickly without any problems or restrictions for her.

Today, Alicia Baier, co-founder of „Doctors for Choice Germany“, criticises the situation for abortions in Germany: “Even the WHO states that abortions have to be provided with as little barriers as possible. And we still have too many barriers.” Since 1995, abortions are exempt from punishment: A pregnancy posing risks to the pregnant woman or evident indications for a pregnancy due to rape allow for an abortion. The third and most common exception is the counselling provision: Until the 12th week of pregnancy, those affected can have an abortion with a doctor, after proving of receiving counselling from a state-recognized counselling centre and a three-day waiting period. However, the paragraph 218 of the penal code, which makes abortions technically illegal, remains.

The Legal Situation in Germany

Paragraph 218 of the German penal code makes abortion illegal. In 1995, §219 was added, which states that there will be no punishment for any abortions as long as they occur within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy and the woman goes to an consultation and adheres to a three day waiting period. Additionally, §219a prohibits the advertising of abortions. This led to big discussions in recent years, after gynaecologist Kristina Hänel was penalised in 2017 for neutrally stating on her website that one of her services was abortion. In 2019, this paragraph was changed so that practices are allowed to state that they perform abortions, however informing about the possible procedures is still prohibited. For many protestors, this compromise doesn’t go far enough

According to Baier, the obligation of a consultation is one of these barriers, as well as the three-day waiting period. “Especially in the countryside, this can delay procedures very much if you have long distances and not only a doctor but also a consultation centre, which you have to go to”, she says. Müller even feels that “sometimes counselling can confuse the women further and shake up a decision already made.” She didn’t have a consultation before her abortion and didn’t feel like she needed one: “Of course I had thought about what I would do if I got pregnant earlier. And I made a conscious decision to say farewell to this child instead of suppressing the situation”, she says.

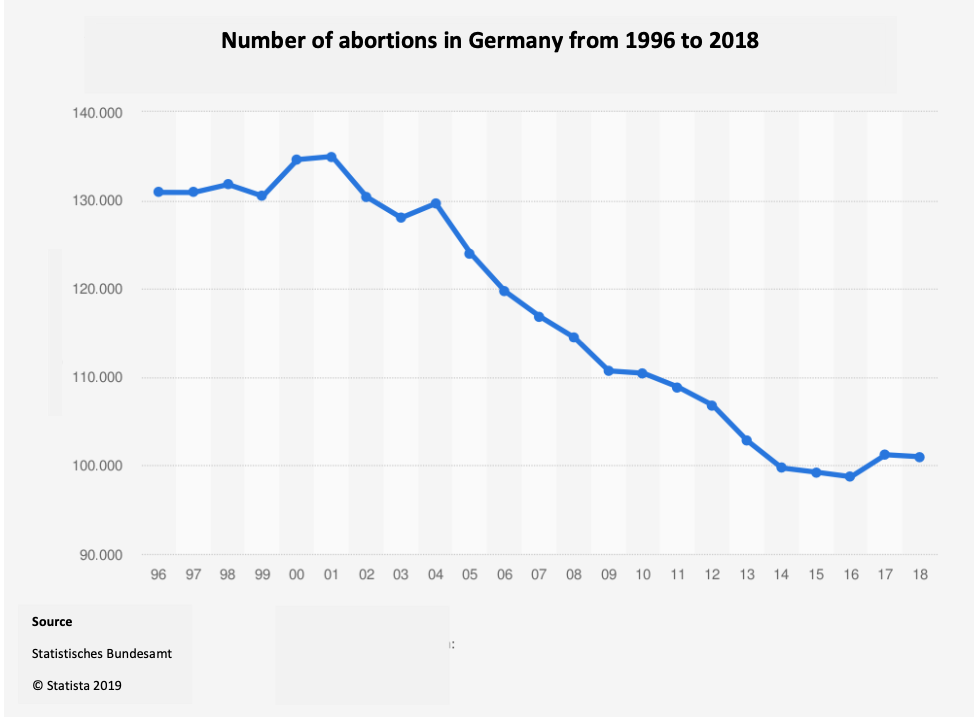

But not just restrictions from the 1990s remain in Germany: In recent years, a decline in clinics and practices that offer abortions fostered the difficulties to have an abortion. In 2015, almost 100,000 abortions were registered in Germany. In 2018, 100,986 abortions were counted across Germany – around two percent less than in the previous year. This has reduced the number of abortions by around 30,000 in the past twenty years. The decline is particularly pronounced in the age group of 18 to 25 year old women, in which most of the artificial terminations of pregnancy are carried out.

Despite a public debate regarding the advertising of abortions in 2018 and 2019 however, the worsening practical conditions for getting an abortion doesn’t produce major public attention or political engagement. Baier assumes that gynaecologists from the older generations, who were still part of the women’s movement, are more politically motivated than her generation to provide abortions. “Another theory would be, that a backlash to conservative values and the classical family model leads to a decline”, the 28-year-old assumes. Anti-abortion-activists, who protest in front of consultation centres, clinics and gynaecological practices and sue gynaecologists in rows by the paragraph 219a have also become an issue in Germany.

Laura Schmidt* who just started her medical specialism training in gynaecology after having finished her studies in medicine, has already performed some abortions. “I think having the possibility to get an abortion is important. That’s why I decided for performing them”, Schmidt explains. “But it’s one of the worst operations for me.” For that reason, she also welcomes the doctor’s freedom of decision for or against performing abortions in Germany. For her, the obligation for consultation is also a good thing: This way women would be aware of what they are doing and not come back to the hospital to have an abortion every other month instead of contraception – which she has heard of and experienced herself.

In general, for Schmidt abortion is just one of many things she has to learn about in her practical training. “It might surprise you how little us doctors think about the political issues of our work. But if we thought about everything too much, we couldn’t do our job anymore and would question things that are not our place to question”, she explains.

Baier, who also just started her practical training in gynaecology, is however one of the more politically involved medical professionals. She compares the situation for abortions in Germany to those in other Western European countries: „Many of those who are against the deletion of this paragraph fear that a regulation of abortion until a certain time wouldn’t be possible without its illegalisation. However, in many Western European countries, abortion is legal, but time limit regulations still exist“, she argues.

During a semester in France, Baier experienced abortions as a much more natural part of the theoretical and practical education and saw political posters about abortion and the women’s right to their body on the walls of the university hospital.

After having protested for trainings in abortion procedures with the Medical Students for Choice in Berlin, she co-founded the Doctors for Choice Germany and also criticises the complete freedom of decision for doctors: “You don’t know, whether most doctors actually make a conscience decision against performing abortions, or saying „no“ is just easier than getting the training or fighting against anti-abortionists. Of course we don’t want to force doctors to perform abortions, but this refusal shouldn’t be so easy, especially for whole clinics or Christian clinic sponsors.”

*Names changed for privacy reasons.

Authors:

Bernarda Carranza is a multimedia journalist from Ecuador with experience in travel journalism, magazine and feature writing, as well as translation and editing. She is an Erasmus Mundus Scholar studying for a Master’s Degree in Journalism, Media & Globalization.

Martin Johaim is an Austrian journalist and proofreader focusing on anthropological journalism in the beats of culture, politics and sports. He is currently finishing his Master in Journalism, Media and Globalization specializing in Media across Cultures.

Jelena Malkowski is a German journalist focusing on migration, culture and society. She studied anthropology and journalism, and is currently finishing her thesis about the perceptions and practices of local and western foreign correspondents based in Uganda.