By Karem Nerio, Laura Kabelka, Tanushree Basuroy and Vanessa Fujihira

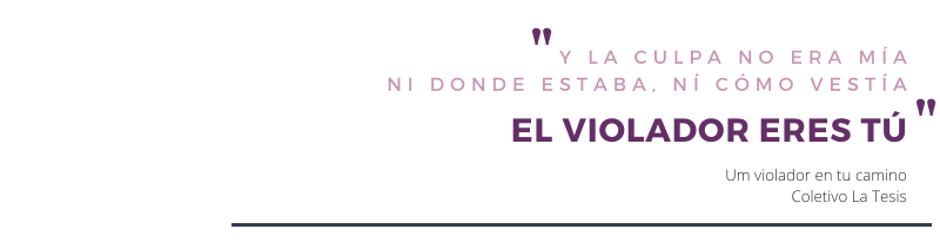

Blindfolded, determined and with a choreography and chant simple but strong enough to spread around the world: The collective “Las Tesis”, in the middle of anti-government protests, took to the streets of Santiago de Chile to shed light on another matter concerning inequality in the country. This time, the focus was on violence against women, including rape and femicide. Their performance was not delivered on just any day, but precisely on the 25th of November 2019, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

The feminist anthem called “The Rapist is You” circulated worldwide and now the message is being repeated in many languages in many places: The blame is not on her – the man is the violator. The lyrics put a character in the spotlight that is not often deeply explored in the coverage and narratives about gender violation and femicide.

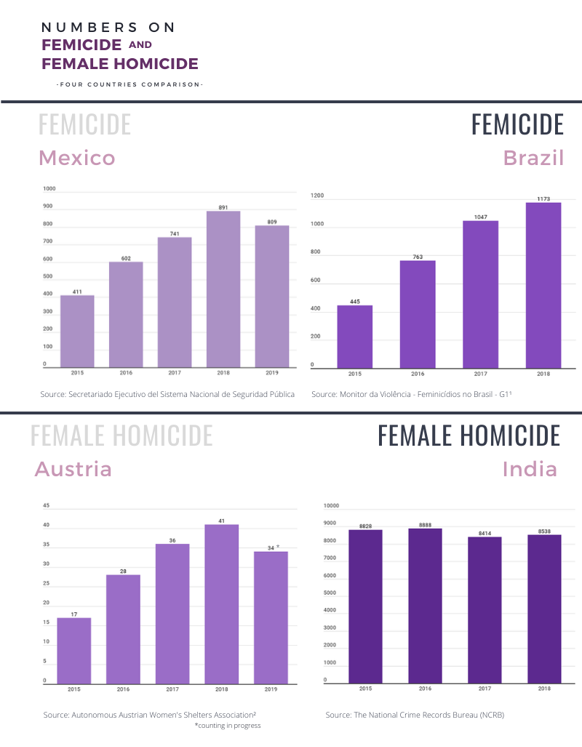

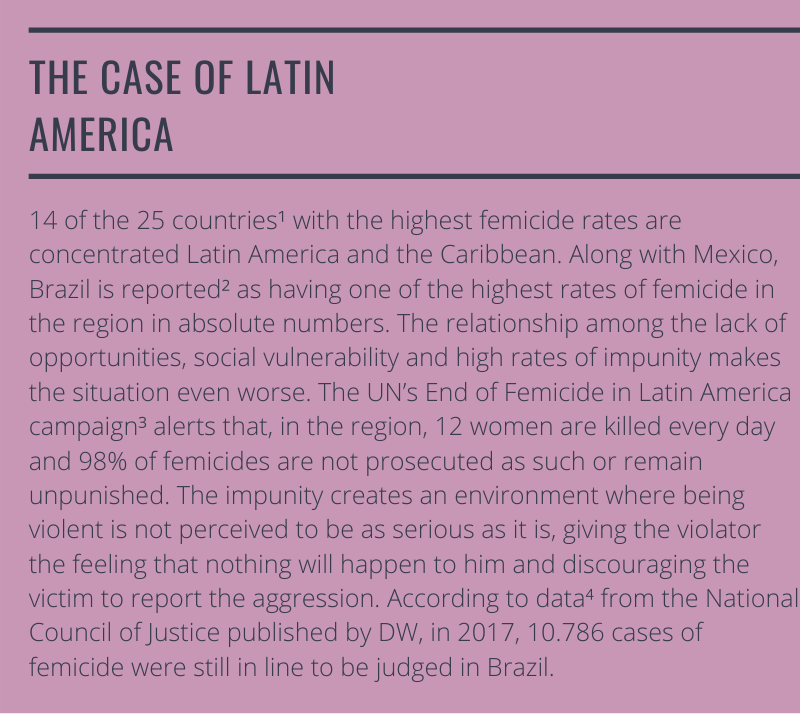

There is a good reason to be outraged about the current situation of women all over the globe: The crimes reported as femicide or gender-related killings are on the rise. From 2012 to 2017, the number increased from 48.000 to 87.000 killings. But the real number could be much higher, since many homicides are not reported or do not go public. How can it be, that so many women are intentionally killed? Instead of regarding the perpetrators of femicide as horrible individuals who went crazy out of the blue, it is shown that these crimes often result from similar relationship figurations and follow comparable steps and patterns. Femicide cannot be attributed to a specific culture in some remote part of the world that we wish to blame for this.

This is where the four of us come in. This cross-border, collaborative journalism project compares and explains the urgent problem of femicide concerning four different countries, each being the home country of one respective journalist: Austria, Mexico, Brazil and India. Talking about the disturbing number of femicides and discussing several cases and discourses in our own countries, we realised that this is a global phenomenon that comes in different shapes but also has many similarities across cultures. Not all countries refer to the problem in the same way, which makes comparisons quite difficult. For instance, Austria reports the crime as female homicide, in India it falls under the broad category of crimes against women, and Brazil and Mexico have specific laws defining femicide.

To understand and depict this issue better, we talked to experts and dealt with data sets and reports. Subsequently, we connected the four aspects of this problem that we see in each of our countries. The part Power issues: blaming the Other concerns Austria where there is a lack of documentation concerning the gender of women’s assassins, but the nationality is very precisely reported and is used to shift blame towards the “Other”, away from Austrian men. Next, we address the construction of masculine identity in Mexican men with Let’s talk about men. Is a non-toxic masculinity possible? Within the same region, in Brazil (The end of a long, bumpy road), although the legal situation has changed and femicide is a clearer term, this has not lead to a decrease of the number of femicide. However, gender education and initiatives such as “E Agora, José?” could make a difference. Finally, in India, Re-looking at the Overlooked: High impunity rates and low rates of femicide reporting, we analysed how femicide is portrayed as a crime of passion and gets reinforced as such via Bollywood movies. In all the cases, we found that men are systematically ignored as part of the problem and even though social movements like #MeToo are rising and creating awareness, there is still an omitted killer in the stories.

Power issues: blaming the Other

The Austrian case

The tendency of an increase in femicide also concerns the small European country of Austria, where from 2014 to 2018, the number of femicides more than doubled from 19 to 41. Although in an international comparison the number looks quite low, this is in fact the highest number over the last ten years in Austria. Moreover, Austria is a highly unusual country when it comes to the proportion of femicides out of all homicides, as unlike most other countries, here femicides exceed the number of murders of men. For instance, out of the total 70 reported homicides in 2018, only 29 were male victims and 41 were femicides. According to Eurostat, Austria even had the highest proportion of women as victims of intentional killings in the EU in 2015.

Using the rate per 100,000 female population, in 2016 the number of total femicide was 0.7 and the intimate partner/family-related femicides 0.5. This shows that women in Austria are often killed by people surrounding them, be it their (ex-)boyfriend, (ex-)husband or a family member. And this is a global reality: While internationally, women and girls account for a smaller share of total homicides, the number of killings of women by intimate partners and family is much higher than of men.

What is documented and what is not

Now, one might wonder about the total number of the year 2019. It turns out to be very difficult to access a more recent documentation of femicides, which should be provided by the Austrian Criminal Police Office (BKA). Although they state that, in general, most culprits are men, they do not keep precise track of the offender’s gender. This lack of record is problematic as knowing who the killers are is essential to understand femicide. In Austria, the term femicide is not commonly used yet and all murders of women fall under the category of female homicide, which is much broader and does not imply patriarchal power structures or problematic relationships as a motive.

In a conversation with Maria Rösslhumer, the Executive Manager of the Association of Autonomous Austrian Women’s Shelter Network (AÖF) based in Vienna, this comes up as a very critical point. “The documentations of the Austrian Criminal Police Office are too vague and many important connections are missing,” she says.

What the BKA document very well, on the other hand, is the country of origin of the offenders: Out of the 76 involved in the fatal crimes of 2018, 41 were Austrian and 35 were foreign citizens. The criminal’s nationality appears to be of particular interest when looking at the news coverage of femicides and the way cases are discussed by the public and politicians. While the cases that are labelled and downplayed as “family drama”, for instance the (ex-)husband or a family member being the culprit, cases where immigrants are the perpetrators provoke a much bigger outcry, and they are depicted to kill because of their “image of women” who should not stand up against men.

The connection to right-wing populism

In 2019, right-wing politician Herbert Kickl seized this as an opportunity to argue that migrants should be deprived of their asylum even for minor crimes and, following the Syrian case in Wiener Neustadt in 2019, where a 16-year-old girl was brutally suffocated and found in a park, he said that criminals should just be sent back to Syria. The politician, who is also notoriously known for statements like “the law should follow the politics”, stated that there would be safe places in Syria, while deporting people back to this war-torn country is illegal due to possible persecution and torture awaiting there.

“Shifting the attention to foreign criminals is a typical, right-wing populist way of inciting fear of the ‘Other’. This does not lead to peace, but more discrimination and it counteracts integration”, Rösslhumer opines. She further describes how it is much easier to find a scapegoat somewhere else and use it as a motive to close Austria’s borders under the wrong assertion of protecting our women. “But violence happens everywhere.”

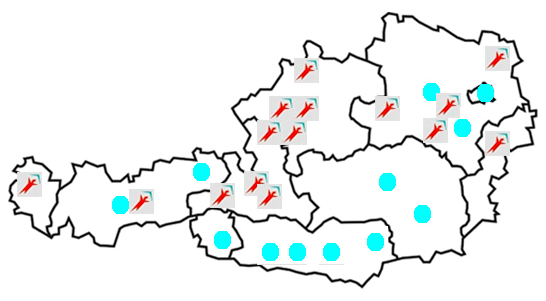

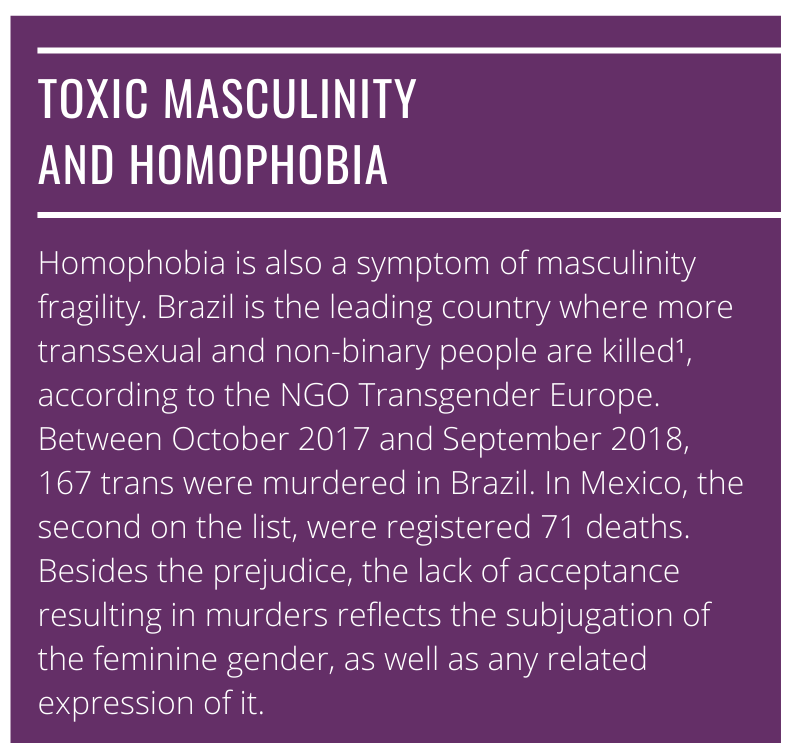

Mapping the situation of men and women

The logic of explaining femicide by a man’s origins is both racist and incorrect, as this issue goes way back before 2015 and the often blamed refugee crisis. Instead, we should get to the roots of the problem: toxic masculinity and violence as a last resort. “Patriarchal thought patterns are sitting very deep, making some men believe that they have a right to control and possess a woman. That’s where we have to begin,” Rösslhumer states. There are only two federal states, Vienna and Styria, that offer anti-violence-trainings. Sometimes, men can choose between detention and these trainings and according to Rösslhumer, many prefer going into custody because they regard it as “the easier way” without confronting their guilt directly.

In the first month of 2019, already 18 women were killed which motivated the Home Secretary to create a screening group to analyse these crimes for patterns, to identify risk scenarios and to derive preventive measures. The screening group consisted of experts from the police, criminal psychology and the Institute for Criminal Law at the University of Vienna. For the 18 cases that were labelled “Intimizide”, a crime committed as part of a relationship, they found that all victims were women and all perpetrators were male. Concerning the motives, the most often occurring reason, with 48%, was unemployment, followed by separation (46%) and alcohol and drug abuse (30%). Further, in 44% of the cases, an entry ban was already imposed on the man and in 16% repeatedly.

What makes the situation for women even more precarious is the way they are dealt with officially. Rösslhumer believes that a possible explanation for the rising number of femicides is that violent actions against women are often not taken seriously and the perpetrators are still running free, giving them an opportunity to strike again. Also, only 10% of the charges get convicted, for instance, because there are contradictory statements of man versus woman. “If women take the big step to report the violence and in the end nothing happens, that is another slap in the face! So it does not come as a big surprise that many women lose trust in the justice system,” Rösslhumer concludes.

So what could be done to improve the situation?

The managing director of AÖF can think of many ways to potentially improve the pending issue. Rösslhumer believes that, primarily, more money and effort should be invested in the protection of women by the state and government. Until 2018, so-called Multi Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARAC) were held in Austria, where women shelters and intervention agencies were involved and cooperated with the police and public prosecutors. “It was a collaborative way to work out how to handle a perpetrator, with solution approaches from various institutions.” Apparently, this was too expensive and there were issues with data protection in the process, but, arguably, this kind of profound cooperation could help protect women from additional violence.

Further, especially in the most dangerous times, such as during a divorce or break-up, women can be very vulnerable and need support. “There has to be more awareness about our women’s helpline. About 200 women call here per year, but more should know about it!” This helpline is frequently used for emergency calls and can be reached via 0800 222 555. Also, there are 30 women shelters all over Austria that serve to protect women and children from violence. Rösslhumer is convinced that campaigns to broaden the knowledge about such institutions could increase women’s safety.

But improving the protection system for women is only half the job. Violent behaviour, the root of the problem, has to be changed. Rösslhumer summarises, “Men have to get confronted and sensitized, and, for this, more resources should be used for improving the work with offenders. The men in question have to start realizing that they have to change, they are responsible, not their children or anyone else.”

Lets talk about men: Is a non-toxic masculinity possible?

The Mexican case

Sonia Pérez was a dance teacher at the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico. She was murdered by her husband on December 9. He turned himself in to the authorities and at his trial hearing, he said he killed her because he saw her talking to another man at a social dinner. This is a recurring story in the narratives of femicides in Mexico, which is a problem that grows year by year. 2019 was the fifth consecutive year at the national level, as in November 2019. This means that every day approximately 10 women are killed just because they are women.

In 17 states of Mexico, the Mexican Government has declared a gender alert, in which public funding is addressed to this issue. Nevertheless, the number keeps rising at a national level. “They have not been effective or efficient,” said María Ochoa, the new head of the National Commission to Prevent and Eradicate Violence against Women (Conavim). The strategy of the current administration, as well as the past ones, has failed to combat this situation.

Every case of femicide in Mexico has a history behind it. However, something that is constantly present and systematically omitted in the stories are the reasons why men commit this crime.

Why do men kill women in Mexico? And is it possible to talk about a change?

According to the aforementioned national statistics, the municipality with the highest number of alleged femicides nationwide is Monterrey, Nuevo León, a city that is located northwest of the country. In this city there are four groups of men who came together to work on the issue of masculinity with different perspectives and approaches, and we talked to one of them.

The group “Amigo Date Cuenta” (Dude, open your eyes), started in September 2019. They meet in public places but also in places like coworking offices every two weeks to discuss a text about masculinity. The group is made up of approximately 10 men, between the ages of 20 and 30, some pursuing undergraduate studies and some with postgraduate degrees.

In Mexico, these groups are citizen initiatives, not necessarily registered or institutionalized. Mexico is not the only country that have this groups, as stated in the Austrian case and later we will present in the Brazilian case. These groups are also in Argentina and Sierra Leona, just to mention a few. In Monterrey, these organizations have their own characteristics. As of December 2019, these are the groups that we tracked: Jóvenes transformado jóvenes (Youth transforming young people) is working on preventing crime in general in polygons of poverty and they also work with the management of violence in young men who had been exposed to narco violence in particular. There is also the group Señores que escuchan (Men who listen), which is a conversational group about masculinity. These two groups address the issue of masculinities from conversations about their personal experiences linked to a feminist theory sometimes.

There are also two groups that come together to discuss the construction of masculinity but from the dynamics of a reading circle. Finally, one of them is a group that studies it from the historical perspective of masculinity and is mediated by Emmanuel Garza, a psychoanalyst at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León.

Gregorio Reyes, member and one of the founders of Amigo Date Cuenta says that the question “What does it mean to be a man?” has chased him for a few years now. He explains that the initiative to start this group arose after a personal process of questioning – what is happening with men regarding the feminist struggle?-. He concluded two things: the first was that he did not want to interfere with the work that feminist activists do, like the sorority attitude or protest like the song “El violador eres tú”, which was also replicated in Monterrey, and avoid any kind of protagonism. The second was that it was necessary to start “working ourselves“, he said.

That is when he decided to invite Franco Arjona to the creation of this collective and they decided to do discussions of texts as a group so that there was a theoretical foundation behind the reflections. They use texts and articles that address masculinity from different topics such as affective responsibility, responsible paternities, romantic love, cis-normativity, among other subjects.

Being a man in a Mexican context, for Franco, is a constant competition. “It is always having to prove that you are a man and live in a very mutilated way with respect to emotions,” he expressed. They say that in their first meeting they used the first chapter of the book “No nacemos machos. Cinco ensayos para re pensar ser hombre en el patriarcado” (We are not born machos. Five essays to rethink being a man in the patriarchy) which in the prologue states: “Only then, looking towards us, we can build another masculinity, free of oppression and violence”.

It is this masculinity, which is commonly known as toxic, which they seek to unlearn. This notion of unlearning is linked to how masculinity is constructed. Because, Gregorio says, they understand it as a social construction for which it is key to understand that “this is how we have learned to be,” says Franco.

They avoid the terms “new” masculinities or “others”, because Gregorio explains that in traditional (toxic) masculinity being a man is linked to being strong, aggressive, violent and in these “new” masculinities -while it is not necessarily- these characteristics it can exercise psychological violence. Then it is not a real change. They are in search of healthy, conscious and free of violence masculinities.

When asked whether there are role models of this type of non-patriarchal masculinity or, healthy, conscious and free of violence, they answer that they have not found someone yet. This process is still in formation and that they claim not to have the recipe. “But I want to believe that there are healthier masculinities,” says Franco.

The challenges of rethinking masculinity

Based on the experience of working in a group, one of the difficulties they identify is the act of listening. Something that they identified is that the men in the group came to monopolize the word and speak for long periods, Franco attributes it to “they are used to always [doing the] talking” and because they have a lot to talk about. After identifying it, what they decided was to implement methods to limit the time and number of interventions per member to give equal time to all. “We do mansplaining because we do not listen,” says Franco.

Another challenge they identified was “there must be an interest of men to understand, open, reflect and then exercise. It is a whole process,” says Gregorio. This motivation to reflect on the responsibility that men have in the face of a crisis of violence, such as the rise in femicide, is linked to putting the practice into action. When asked why they believe that the index of impunity in Mexico is large in crimes related to gender-based violence, especially femicide, they first answered “lack of attention from all parties involved (in the justice system) and much that we let go. Among men, when one is silent and everyone is making sexist jokes, that’s where you have to put the action in.” “Don’t just say I am this or I believe this, the most important are the day-to-day actions where you can stop the patriarchy,” said Franco. They link the small actions to a bigger crisis like this one.

In this transition between what should be and the everyday practice, the thing that has helped a lot is to ask each other, they explain. In this dynamic, trust networks are formed between men, a kind of network is very different from a patriarchal pact – where there is trust between men but it may be that the violence is predominated. It is in those groups where men, they explain, can have to take responsibilities.

“Take responsibility”

After a few months now, the group has developed some reflections about their work, which Gregorio explains like this: “Dude, now that you are questioning for yourself all this also take full responsibility for it. If you have to take responsibility for your education about this macho culture and learn another way more healthy, conscience and free of violence. And contribute from yourself and your experiences.”.

This group is committed to working on masculinity from a face-to-face and virtual strategy, because in addition to the reading circles, on their Facebook page, the group shares memes about this type of masculinity. Something they called “drip activism. “A meme for you to deconstruct yourself”, he said.

Although they identify that the profile of the members of their group has a series of privileged conditions with respect to the Mexican context and a medium socioeconomic level, they emphasize that more new groups are needed to detonate this conversation in other surroundings of Mexican society, such as in fatherhood.

The end of a long, bumpy road

The Brazilian case

In one of the most emblematic cases of femicide in Brazil, Eloá Pimentel, 15, was held captive and killed by her ex-boyfriend, Lindemberg Fernandes, 22. The reported reason: he did not accept the end of the relationship. This episode was extensively covered by the media that spectacularized the hostage crisis and murder of Eloá. Back then, in 2008, the intentional homicide of a woman motivated by gender was not called femicide. Instead, the idea of crimes like this as “passionate crime” – the one motivated by love – was widely spread.

According to the Map of Violence 2015, Brazil occupies the 5th position in the number of femicide worldwide. Although femicide was already present, it was just in 2015 that the crime was typified as such. The “Femicide Law” defined the delict and included it in the list of “heinous crimes”. Calling the femicide by its name helps to better identify the phenomenon and to clarify that the killing is motivated by the victim’s condition as a woman. It also helped to slowly move media, public opinion and judiciary away from the idea of femicide as a crime motivated by passion instead of gender hate. In addition to the “Maria da Penha Law” of 2006, that protects women against domestic and family violence, the Femicide Law represents progress in the legislation, but not necessarily reflects in a decrease in the crime rates.

But who is killing our women?

Following a tendency that also occurs in the other four countries, it is calculated that in 50,3% of female homicide cases the culprit is a current or former partner or even a family member, many times in a domestic context. When it comes to femicide, a study showed that 88.8% of perpetrators are partners or ex-partners. This type of crime is called “intimate femicide” and is often linked to possession, jealousy and objectification of the female body. In many cases, the man does not accept the end of the relationship or claims that it was the woman who provoked the aggression.

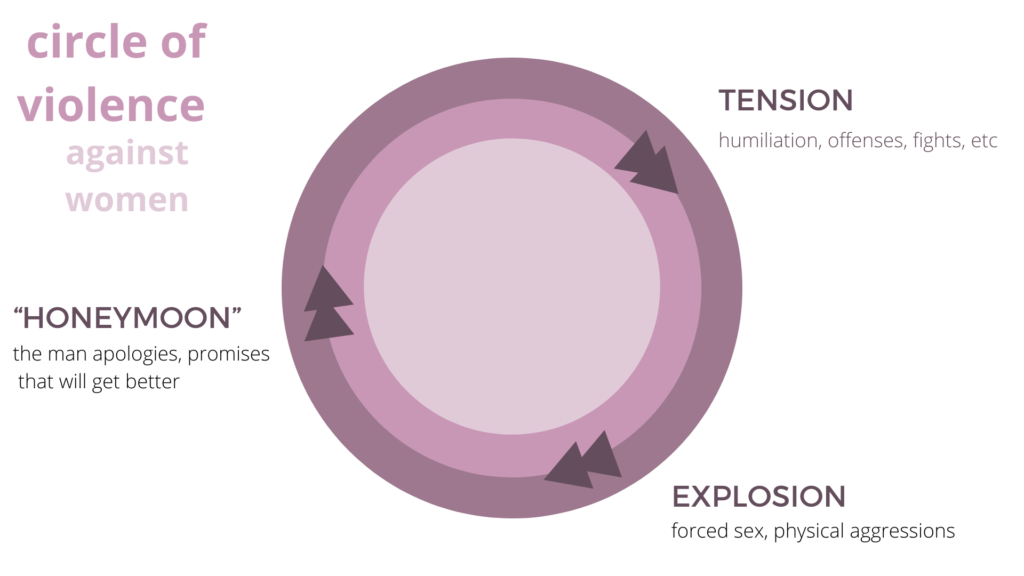

However, femicide is often the last stage of a long road of prior gender violence instead of an unpredictable act. The Brazilian Institute Patrícia Galvão compiled some important data showing this: 503 women are assaulted per hour (2017), 5 are beaten in every 2 minutes (2010), 1 rape happens in every 11 minutes (2017), and 1 woman is killed in every 2 hours (2017). At the same time these numbers have shown an escalation of the violence until a no way back, it also tells us that preventing female assaults and domestic violence could interrupt a circle of violence. When it comes to femicide, there are 4,8 gender-motivated homicides per 100 thousand women, putting Brazil on the top of the list worldwide.

In an interview for the Brazilian news portal G1, the psychologist Paulo Patrocínio explains that, in general, the aggressor is perceived as a “common citizen” and domestic violence is so impregnated in our society that it becomes almost invisible. Patrocínio sees the violence against women as a vicious circle that is interrupted in two ways: the end of the relationship or the femicide. This circle is explained in three major steps: a) tension (humiliation, offenses, fights, etc), b) explosion (forced sex, physical aggressions), and c) “honeymoon” (the man apologises, promises that it will get better). Then the circle begins again.

Let’s talk about being a man

Flávio Urra is a psychologist and sociologist who coordinates the initiative “E Agora, José?”, a reflexive group focused on men sued by the Maria da Pena law on domestic violence. Since 2014, every week, two groups of 20 men each gather together in Santo André, in the metropolitan area of São Paulo, to talk about masculinity, gender, and violence. The normalization of violence is so evident in Brazil, that many of the authors of aggression do not even recognize their acts as a crime. “When they arrive in the group, their discourse is first characterized by resistance. Many feel they are being wronged or cannot identify they were violent. And when they do, it is in a defensive form: a common tendency is to blame the women”, explains Urra.

As a result of a partnership with the judiciary, the men accused of psychological, moral or “light” physical aggressions are driven to the dynamics as part of the punishment. With a duration of 26 sessions, the initiative already assisted 300 men. The process is long, but the outcome is quite positive: the level of reported recurrence is almost null and after the seventh session or so their discourses begin to change. “The men start to regret and to understand topics as sexism, gender oppression, men privileges and also prejudice against the LGBT population. Here, we focus on the responsibilization of their own acts”, shares the coordinator.

Through the analysis of the discourses and application of questionnaires about gender, a change is observed from the use of common sense ideas about gender roles to a more sensitive and independent, reflexive discourse. In the group, the participants learn about what it means to be a man, questioning notions of toxic masculinity. The “E agora, José?” experience shows the importance of gender education to start to change this reality and shape a new idea of masculinity.

In this context, it is important to discuss and teach gender equality and diversity to girls and boys. In this way, from an early age, children can learn the limits of the other’s body and also identify abuse. The debate about gender education in schools is currently a controversial topic in Brazil, with high resistance to the conservatives and religious bench. Nevertheless, gender education in schools can be a tool for femicide prevention. According to Luiza Cristina Frischeisen, gender education has to start in school and at home with the family, to reinforce that girls have rights and to dismiss the idea of objectification of the female body.

Who is dying, who is killing

A detailed profile of who the aggressors are and why they kill is necessary. At the same time, observing who the victims are allows us to understand some dynamics related to masculinity, violence, and exercise of power (or weakness). In Brazil, the intersection among race, class, and gender is revealed in the following femicide numbers: 61% of the victims are black and 70,7% studied just until the elementary school, according to the Brazilian Public Safety 2019’s Yearbook. Black women also represent 60% of the calls to the Brazilian helpline against domestic violence and homicide numbers of black women have increased by 22% against a 15% decrease in the femicide of white women. This data compilation from Artigo 19 shows that the sad reality of inequality and racism is also reflected in the femicide rates.

Although data reveals a generalized killing of women, with escalations inside some minority groups, it is more difficult to trace the killer profile. One of the reasons is that it is not just an individual act, but a projection of systematic gender hate. The aggressor seems to be the common man. “In the reflexive group, the profile is diverse. Many create an image that it would be a group of “monsters”. But no, there is no stereotype attached: what we see is a group of normal, everyday men,” elucidates Urra from the reflexive group experience. As an example, the youngest man in the group is 20 years old, while the oldest is 95. Some do not know how to write, some have a master’s degree. They are businessmen, workers, soccer players, lawyers, policemen. They are the ex-boyfriend, the current husband. Potentially, they can be any men.

Re-looking at the Overlooked: High impunity rates and low rates of femicide reporting

The Indian case

Think of India and the images that flash through one’s mind are those of a vibrant people and culture with colourful garbs, zesty cuisines and, of course, Bollywood. A land that deifies women and worships the female energy as The Mother. But a darker tale underlies the streets teeming with the world’s second largest population, nearly 49 percent of which is accounted for by women (Central Statistics Office). It is these very streets that women are asked to beware of, be it at night or day, lest they become prey to the voracious appetite of the other sex’s desire or rage – “passion” nonetheless. The term femicide is often touted as a “crime of passion”, leading to a certain romanticization and sensationalization of the phenomenon. A 2015 study by Canadian scholar Myrna Dawson, titled ‘Punishing femicide: Criminal justice responses to the killing of women over four decades’, concluded that such nomenclature draws away from the heinous nature of the crime, Bollywood, too, taps into this tragic reality, churning out box-office winner crime mysteries and thrillers such as No One Killed Jessica and Talvar.

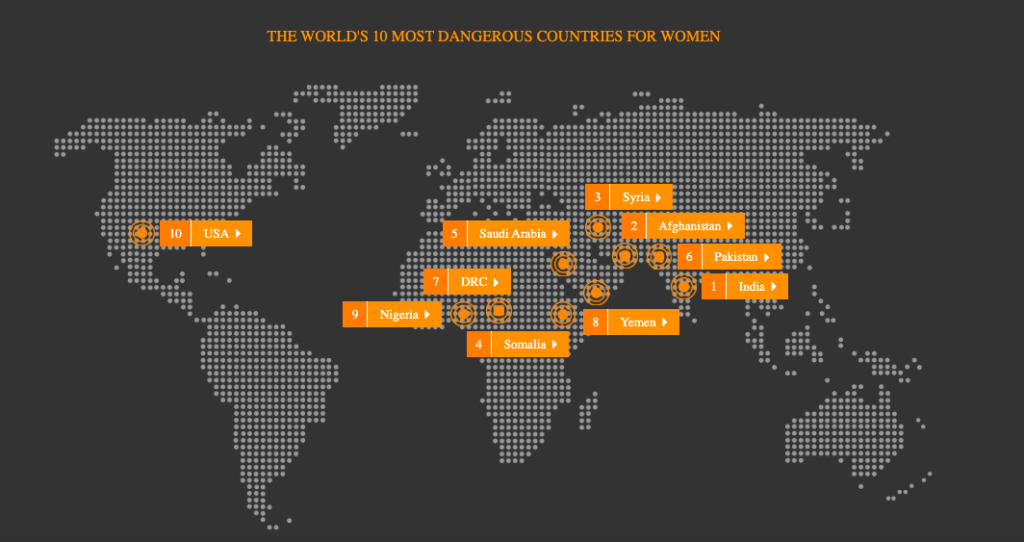

Although the Thomson Reuters survey conducted in 2018 ranks India as number one among the top ten most dangerous countries for women, leaders have much to show for the grand promises made concerning women’s safety. “It is linked to patriarchy and women are accorded a secondary status” explains social entrepreneur and founder of Red Dot Foundation, Elsa Marie D’Silva. “Lack of financial independence, dependency on male family members and socio-cultural factors that glorify women but don’t make her human enough to have agency is the issue. There is a clear preference for a male heir and therefore there is a high rate of femicide” she elaborates.

Punishing femicide

As reported by the Economic Times, the number of reported cases of crimes against women increased since the 2012 Delhi gang-rape case but the rate of reporting has once again been on the decline since 2014. It was noted that crimes against women account for 10 percent of all crimes registered under the Indian Penal Code, but only accounts of molestation have seen an increase in reporting since 2012 while other accounts of sexual violence remain largely under-reported.

Meanwhile, the phenomenon of femicide seems to have been missed by the searchlight of both law enforcers and researchers in India. While the World Health Organisation provides a broad understanding of femicides as being the “intentional murder of women (and girls) for being women”, the Indian Penal Code categorises the phenomenon in terms of murder or within the overarching term “crimes against women”.

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported 7,693 women and 721 girl children murdered in the year 2017. There were 227 counts of murder with rape or gang-rape, 7,838 counts of dowry deaths and 5,467 reports of abetment to suicide of women categorised under the Crimes Against Women section of the Crime in India report by the NCRB in 2017.

In fact, according to the typology provided by WHO, honour-related and dowry-related murders are the most common forms of femicide in Asian countries. This goes beyond the standard notion of femicide being a crime of passion carried out only by an intimate partner. However, the findings of Dawson’s research suggest that intimate or familial femicides are treated more leniently leading to higher impunity rates. Moreover, political clout seems to go a long way in the fast tracking of such cases and acquittals as was seen during the nascent stages of the Jessica Lall murder trial in 1999, where the culprit was the son of a member of the Indian National Congress party.

A Culture of Toxicity

While it must be acknowledged that there have been many improvements in India with regard to women’s empowerment post-independence, there is still much to be done in terms of gender equality within Indian society. The problem appears to lie systematically within social structures that propagate patriarchal norms. It raises questions of what might drive men to commit an act that lies at the “end of the spectrum” of the violence and abuse meted out to women.

Dr. Itisha Nagar, an associate professor at Kamala Nehru College of Delhi University, attributes the reason as to why men hit women to a “dual thinking” that exists within Indian culture today. “Men are seen as protectors and there is a socio-cultural sanction given to them to violate women, especially if the women are seen as not standing up to the ‘ideals’ upheld by society” she elaborates. Backed by society, men believe they are responsible for keeping women in check, that is, through violence.

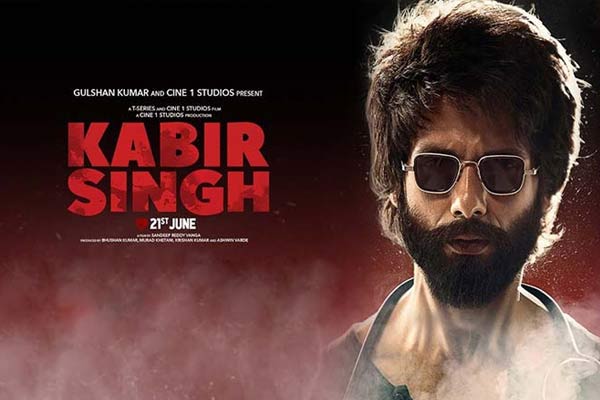

One of the many ways one might find society endorsing such toxic behaviour is through Bollywood. The massive and world renowned film industry has become more than just a by-product of culture but a guide to everyday lifestyle. Songs and movies right since the 1960s to date have a deep impact on the audience. Dr. Nagar adds that social acceptance is openly exhibited that allows men to get away with degrading behaviour. A recent example of the glorification of toxic masculinity, patriarchy and misogyny was the Bollywood movie titled, Kabir Singh, that caused much of an outrage for glorifying rape culture under the pretext of heartbreak and the male protagonist expressing intense emotion through his abusive ways.

This is a point of poignancy where the very men who are socially sanctioned to be aggressive towards women, are “emotionally castrated” by society. Dr. Nagar explains that men do not know how to express their emotions, except in terms of anger and aggression for fear of being viewed as less masculine. “Gender roles as constructed by society demand that women act as being pitiful and thoroughly dependent on the different patriarchal figures around her, while men are denied a chance to explore different aspects of their being and made to internalize notions of masculinity such as ‘men don’t cry’. Often more articulate men are immediately associated with being homosexual or “pansies” which does not line up with the hypermasculine ideals constantly reinforced by society and pop culture. However, it must be reiterated that this does not absolve men of the blame and they must still be held accountable for their actions.

Treading the path to a safer future

Ms D’Silva concurs, stating that “[it] is toxic masculinity that is responsible for most of the violence. Helping men understand their own responses, biases and respecting consent and choices of women is important. Education plays a big role and it needs to be incorporated into the educational curriculum at an early age.” The founder of Safecity, a global platform that documents sexual harassment and violence in public spaces, both practices and recommends “conduct[ing] extensive awareness workshops in schools, colleges, corporates and communities explaining gender stereotypes, challenging biases, understanding the spectrum of abuse and helping decode the various legislation in effect” as measures to building a safer society.

However, the social sanctioning of violence against women mediated through Bollywood and the high rate of impunity are factors that might make victims and their associates desist from reporting the incident. Ms D’Silva emphasises the vitality of information, “encouraging people to share their personal stories anonymously on sexual violence which forms a database that can be mined for patterns and trends at a local level. This is open sourced and available to individuals, communities and institutions to access and develop their own solutions.”

With progress being made at the pace of “one step forward but two steps back”, it remains to be seen how soon India is able to erase the label of “the world’s most dangerous country for women”.

Authors:

Tanushree Basuroy is an aspiring travel journalist from India currently enrolled in the Erasmus Mundus Master’s program for Journalism, Media & Globalization.

Vanessa Fujihira is a media and communication professional from Brazil and student of the Master’s in Media and Journalism across cultures in University of Hamburg.

Laura Naima Kabelka is an aspiring Austrian journalist with a special interest in covering globalization, cultures and individuals’ stories.

Karem Nerio is a freelance journalist from Monterrey, Mexico. She has worked for El Norte, Agencia Bengala and also in independent journalistic projects.